Exploring the intersection of spaceflight history, pop culture, and space art.

This edition of Creating Space examines various ways in which space artists have missed the mark when it came to accuracy in their illustrations and paintings. So, buckle up – we’re blasting off on a Space Art Oddity tour!

Are you new to Creating Space? It’s the NERDSletter that explores the intersection of spaceflight history, pop culture, and space art. You can find this and all other posts at creating-space.art.

The Stars Look Very Different Today

This edition of Creating Space introduces the concept of Space Art Oddities.

Call them what you wish – oversights, mistakes, goofs or outright blunders – space art oddities1 are things that look out of the ordinary or unexpected in works of space art.

Specific examples might be illustrations in which the Earth is depicted without any clouds, or that have the sunlight coming from multiple inconsistent directions, or when space vehicles are simply drawn wrong. I have seen all of these things in various works of space art – sometimes from prominent and accomplished artists.

If you have read this blog’s first introductory post, you know that this is a topic that – perhaps oddly – interests me. From time to time, I will share some of these space art oddities with readers of Creating Space. The first of these is truly out of this world.

You’ll Get a Blast Out of This One

To help you visualize what I am describing, I have chosen an example from the 1960s that exhibits all three of these odd characteristics – and more.

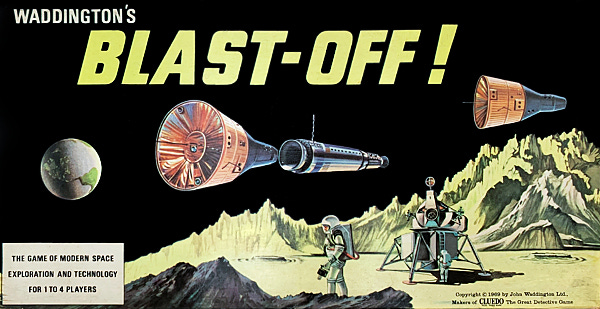

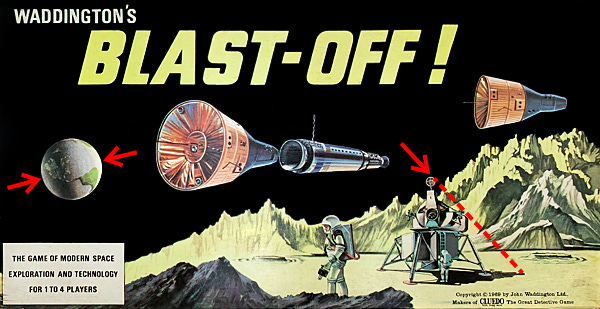

BLAST-OFF! is a board game that was first sold in 1969, around the time of the first manned Moon landing. The banner on the box proudly proclaims itself as “The game of modern space exploration and technology”. We’ll see just how modern this game really was.

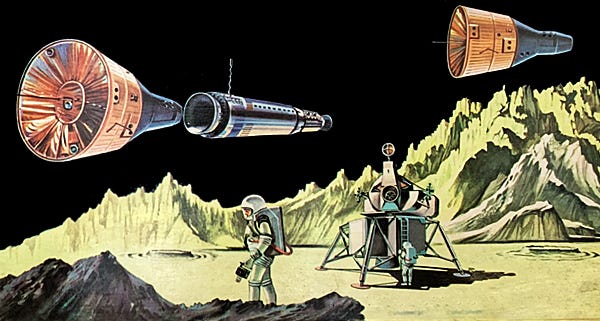

The box-top artwork is quite a sight to behold. There’s a lot going on here, so let me break it down.

The scene depicts two astronauts engaging in extra-vehicular activity (EVA) outside their Lunar Module (LM)2 which has landed on a clear, level plain bordered by sharply peaked mountain ranges. The Earth hangs in the starless black lunar sky.

All seems quite normal so far. Or does it?

One can’t help but notice some things that are a little odd about this illustration. Can you spot them all? Let’s take them one at a time ...

By the way, I mean no disrespect for the artist who created the box illustration. They were given an assignment, likely on a short deadline, and even more likely with specific art direction to follow. Everything has been executed faithfully and is easily recognizable. Plus, being a game, complete accuracy was probably not the goal. More likely, the goal was to create something eye-catching that might capture the imaginations of kids, and convince Mom or Dad to buy it for them. Having said that, let’s have a little fun with what we see here.

Lunar Gemini

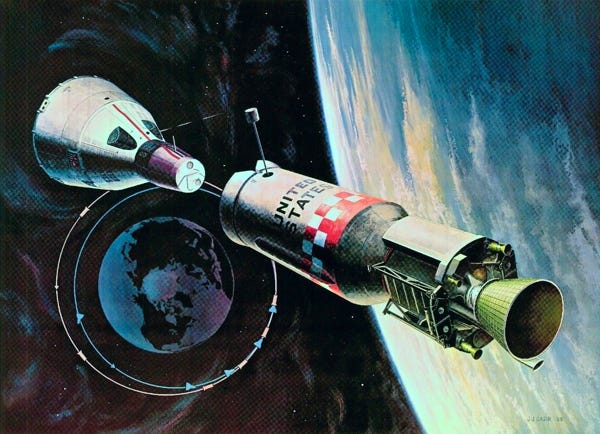

By far, the most attention-grabbing aspect of this box art has to be the two Gemini capsules and the Agena spacecraft looming large and low over the heads of the astronauts – who, incidentally, seem oblivious to what is happening right above their helmets.

There are at least two questions we can ask.

Why Gemini?

... and ...

How fast would they be going?

To address the Gemini question, first, the game uses player pieces that resemble Gemini and Agena spacecraft. That may be the main reason why they are depicted on the box.

But, did you know there is a historical connection between Gemini and the Moon?

The Gemini program flew missions between 1964 and 1966, and was conceived as the way NASA would learn to do everything necessary to achieve the upcoming Apollo missions to the Moon. Those things included long-duration missions, orbital maneuvering, multiple spacecraft rendezvous and docking, extra-vehicular activity (or, space walking), performing useful work in space, developing and perfecting re-entry and landing methods, as well as testing and evaluating as a host of new technologies, equipment, and procedures.

While those missions were designed for, and executed in, exclusively Earth orbit, there were some discussions about using a Gemini capsule as a Moonship.

To adequately cover the many variations of Lunar Gemini would require volumes. Other space history articles345 have done an excellent job of describing the multitude of proposals for using a Gemini capsule as the basis for getting to the Moon by the end of the 1960s. I encourage you to read the articles listed in the footnotes.

Indeed, expediency was one of the major motivations for most of those proposals. Proponents of such schemes argued that the Gemini spacecraft was already developed and had a proven record of success. They also noted that the smaller, lighter capsule, coupled with the fact that it carried only two men, meant that smaller boosters could be employed and therefore might make the development of the huge Saturn V rocket unnecessary.

Various boosters and upper stages were considered to get a Gemini capsule to the Moon, either in a direct shot or via rendezvous in Earth orbit – Titan II, Titan-IIIC, Centaur upper stage, Saturn C-3, Saturn IB, and even the Saturn V. Associated with these boosters would be either specialized mini lunar modules launched separately and docked to a Gemini in Earth orbit or an augmented Gemini to serve as a lunar lander.

Given that some of these approaches required the Gemini to dock to a booster stage to reach lunar altitudes, it may not be so far fetched that the BLAST-OFF! game uses Gemini/Agena couples as game pieces.

Fast and Curious

The second question regarding the Gemini vehicles on the BLAST-OFF! box is, how fast would they need to be going to remain in such a low lunar orbit (assuming, of course, they don’t encounter any mountains or high crater walls)?

After treating myself to a little refresher on orbital mechanics, I worked up a quick little spreadsheet to calculate orbital velocities.

Using the astronaut near the LM as a scale reference, it appears that the Gemini and Agena spacecraft are maybe about 20 feet (6 m) above the surface. Using the orbital mechanics equations I found, it works out the velocity needed to maintain orbit at that height above the Moon’s surface is roughly 3,760 mph (6,050 km/h). That’s fast, especially when you are that close to the ground! The lunar traffic cops would definitely be handing out a couple of space speeding tickets in this case.

For reference, Apollo orbited at an altitude of about 60 nautical miles (110 km) and a speed of close to 3,650 mph (5,860 km/h). Interestingly, if I have done my calculations correctly, Apollo’s orbital velocity was not that different than that of the extremely low Gemini capsules.

I Can See Clearly, Now

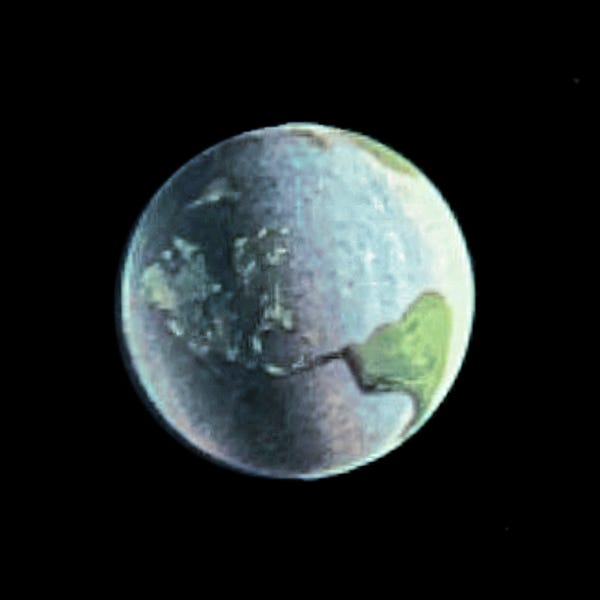

The Earth depicted on the BLAST-OFF! box appears to be devoid of clouds. Not only that, but it looks strangely devoid of water, altogether. But, I am sure that just may be a result of faded colors on this half-century-old box.

Here’s a color adjusted version of the Earth ...

If anything, there might be too much water on this globe. Look at what appears to be a great sea covering much of the eastern central United States. Could this be a prediction of future sea level rise? I don’t know. For now, let’s focus on the lack of clouds.

I am fascinated with how early illustrations of Earth from space very often showed no clouds. Artists, I would think, knew intellectually that clouds existed and could be seen in the sky from below, but did they think they would somehow be invisible from space? Apparently, Earth had world-wide perpetual sunny weather if the artists (with a few exceptions) were to be believed.

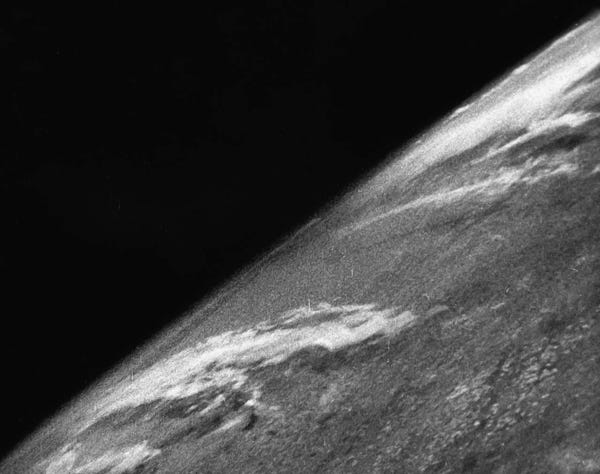

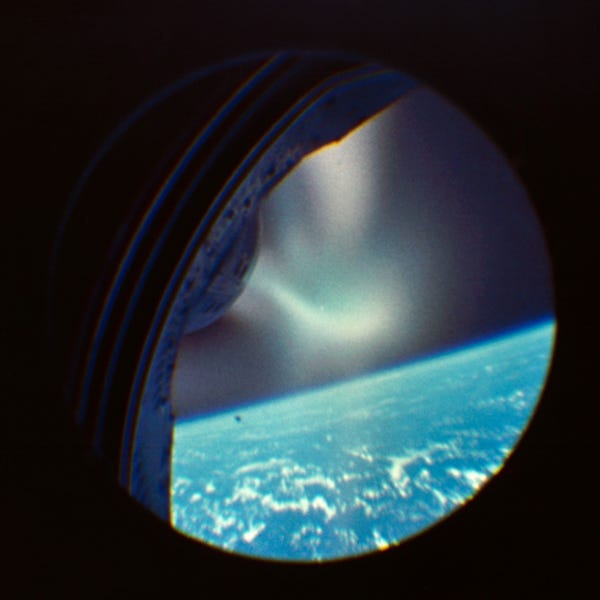

Cameras lofted into space delivered photographic evidence to the contrary. In 1946, high above White Sands, New Mexico, a camera mounted to a captured German V2 rocket came back with this image.

Fifteen years later, a select group of astronauts and cosmonauts began to witness the cloud-covered Earth with their own eyes. Here’s a great shot of Buzz Aldrin in the open hatch of his Gemini 12 capsule, while docked with an Agena. The beautiful blue globe of the Earth, dusted with bright white clouds, serves as the backdrop.

Shining a Light on the Subject

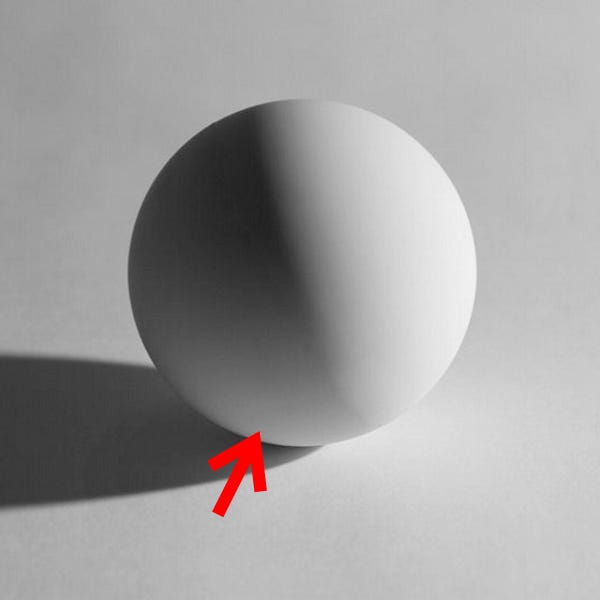

Some early works of space art display a meticulously rendered moonscape, for example, showing off accurately depicted details of a spacecraft and surrounding rocks and craters. The artist might have a planet in the black sky above. If you look for it, you might notice something odd in some of these paintings. It might dawn on you that everything in the scene is lit from one direction – except for that one planet up there.

As you might have guessed, the BLAST-OFF! box art contains just such a goof. While the lighting and shadows on the lunar mountains and the LM are consistent with each other – indicating the Sun’s position high and to the left of the scene – the objects in space appear to have their own independent light sources.

The Earth shows a main light source coming from the right, with that half of the hemisphere brightly lit.

Interestingly, there is another hint of light on the left side. This is an example of a classic drawing and painting technique for still life renderings. If you picture the Earth as a ball sitting on a table and lit from the side, there will be a bright side and dark side, as expected. Additionally, there will be subtle gradations of light and shadow. A lighter area will be caused by light bouncing off the table onto the ball, and darker areas will be seen in places where shadowed surfaces meet.

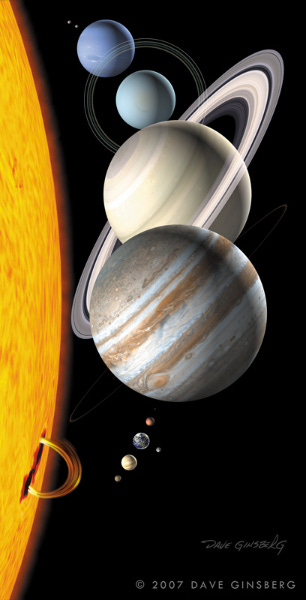

The box artist may have been falling back on his classical training in this case. I must admit that I, myself, have fallen victim to this temptation. The solar system mural I created for the Museum of Flight in Seattle, Washington, has lighting coming from two directions – the main light source on the left and a secondary rim light on the right. This was an artistic choice on my part. I felt the addition of the rim light enhanced the look of the image and help separate the planets from the black background. The museum exhibit designers accepted my use of artistic license, in this case.

For Here Am I Sitting in a Tin Can

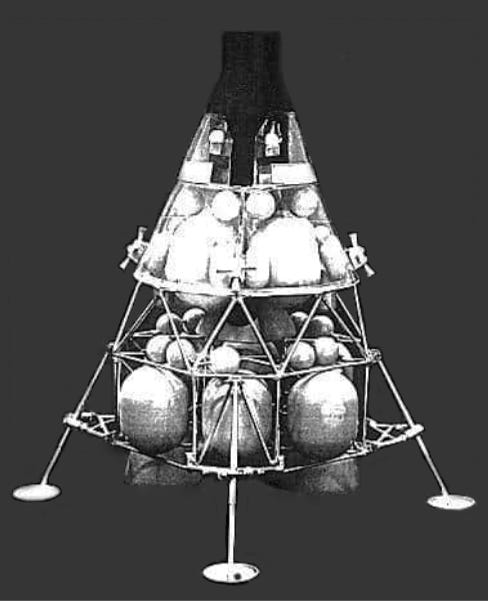

Another common oddity I see often is misdrawn spacecraft – most frequently, the Apollo Lunar Module. Now, I will be the first one to recognize that the LM is not the easiest thing to get right, with all of its angular shapes and irregular facets. But, some of the depictions I have seen really mangle that poor little bug beyond what might result from trying to draw complex geometry.

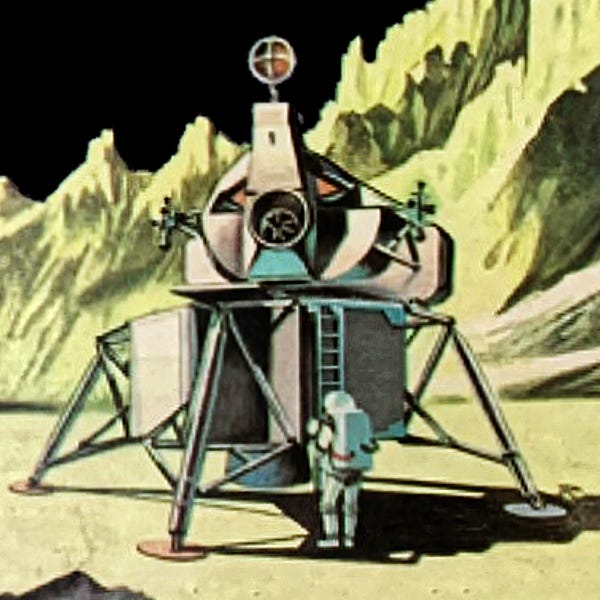

Take, for instance, this LM. To be fair, if you take the ascent and descent stages separately, they are each represented fairly well at first glance. But, for some unknown reason, the two stages appear to be out of alignment with each other. Maybe they experienced a very hard landing.

Looking closer, though, some odd features begin to jump out at me. For example, why is the front ‘cheek’ of the ascent stage, below the Commander’s window, jutting out so far? And what exactly is going on with the lower leg struts? I’m beginning to think the artist may have been assisted by Pablo Picasso.

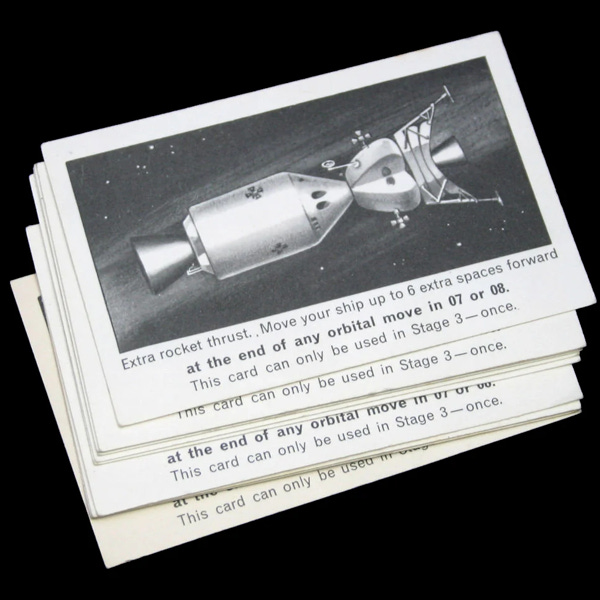

Inside the box, there is another example of an oddly-shaped Lunar Module (LM). The game contains a stack of cards that players may use to give extra ‘rocket thrust’ to their pieces. Each card contains an illustration of an Apollo Command/Service Module (CSM) docked to a Lunar Module. Let’s set aside the odd mix of Apollo imagery with the other Gemini references in the game. The LM is a truly unique rendition among those that I have seen elsewhere. In this case, the artist didn’t even try to attempt to draw the complex angular shape of the LM ascent stage. Instead, there is something that resembles an apple with a section sliced out of it – complete with seeds and all!

Drawing Conclusions

There are more things I could say about the artwork on the BLAST-OFF! box. For instance, I could point out that the lunar mountains are steep and sharply pointed, even though by 1969 it was well known that the Moon had rounded, undulating hills due to impact erosion by meteorites. My guess, judging from the early configuration of the LM and the space suits, is that they may have chosen to save some money by using artwork that had been done previously. I could also ask why the lunar surface is yellow (cheese?). But, I understand artistic license and the fact that bright colors are better for marketing.

Rick Armstrong once shared, during a public talk, what it was like watching TV and movies with his father, Neil. There wasn’t a single error that would go by without Neil pointing it out. I think this is a common trait among engineers. We naturally see factual mistakes and logical inconsistencies. And, because of our particular (dare I say, peculiar?) social skills, we sometimes can’t help but point them out.

I find myself doing this all the time, as well. I know that I may drive people crazy by doing this, but it is a sickness for which I know no cure. I can’t tell you how many times I have seen rockets miraculously change from Redstones to Atlases to Titans to Saturns during launches when the camera angle changes. One of my biggest peeves is hearing a narrator talk about the Apollo Translunar Injection (TLI) while the video clearly shows the view out of a Gemini window of the trailing plasma during the heat of reentry. (They sometimes even dub the sound of a rocket engine over such erroneous video. Argh!)

As an artist and designer, I think this – let’s call it either a superpower or a curse – extends into the visual realm. I can’t unsee uneven text kerning. Not a crookedly hung picture escapes my glance. I can’t help but see inconsistent Sun angles and cloudless Earths. And, ever since I first noticed incorrectly drawn Lunar Modules, I find them everywhere I look.

Now, you too have this superpower. You’re welcome. Please, use it to do good in the world.

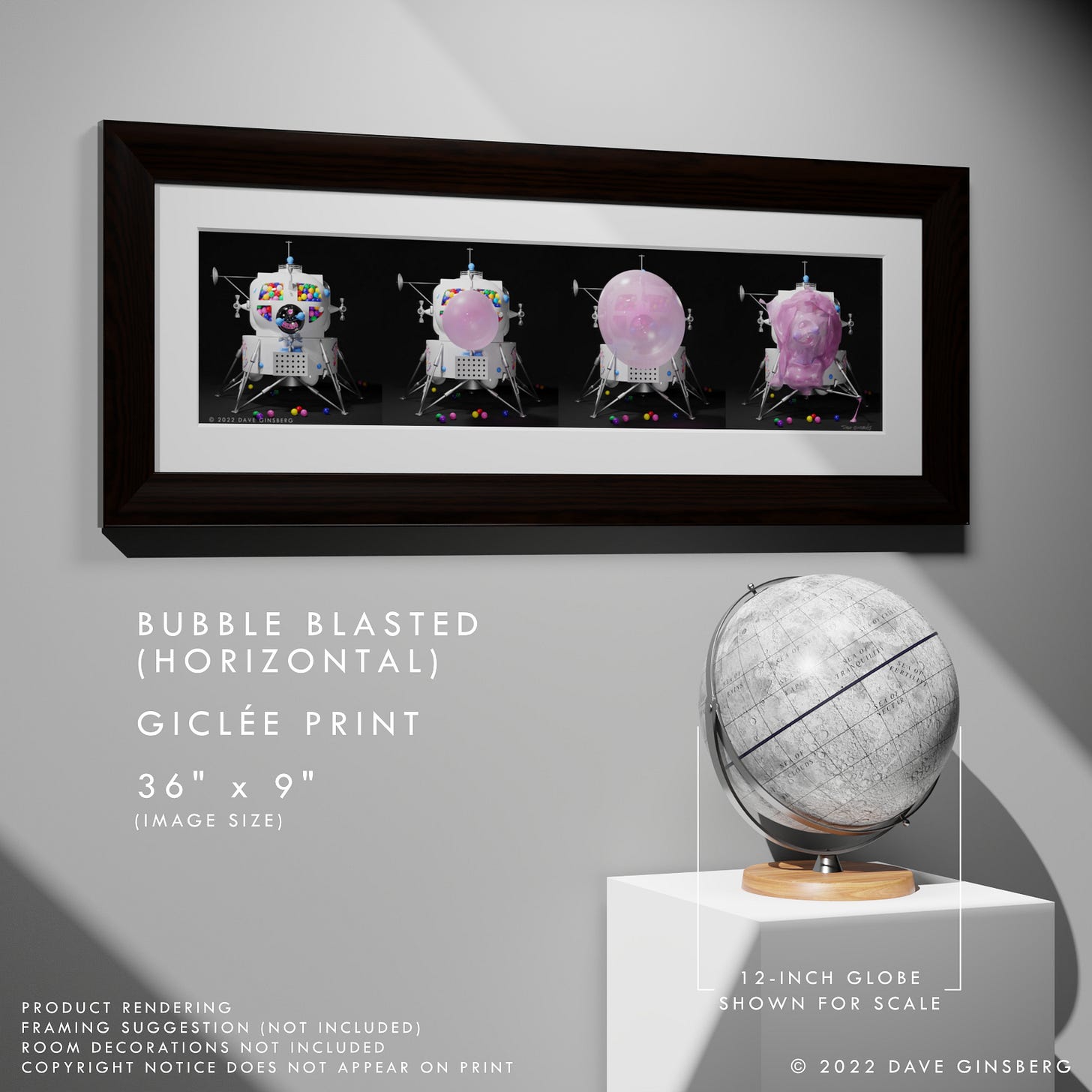

Merch of the Month

Bubble Blasted (Horizontal) Giclée Print

At first glance, this may look a little odd, but I assure you that the lighting is consistent and the LEM is accurate*.

(* Except for the bubble gum, of course.)

As a special thank-you for reading Creating Space, I am offering a discount on my artwork. Simply use code CREATINGSPACE15% for 15% off your entire order from the Pixel Planet Pictures shop.

My space-inspired art portfolio can be found at pixel-planet-pictures.com. You can also follow me on Instagram (pixelplanetpics).

Do you know fellow Space Geeks who might enjoy Creating Space? Invite them into this space, too!

Did you miss a post? Catch up here.

If you enjoyed this article please hit the ‘Like’ button and feel free to comment.

All images and text copyright © Dave Ginsberg, unless otherwise noted. All rights reserved.

With apologies to David Bowie.

I am using ‘LM’ here, rather than ‘LEM’. In June of 1966, NASA dropped the word ‘excursion’ from the name of the lander.

Gemini: Lunar Gemini, Encyclopedia Astronautica, Mark Wade

Two to the Moon: Lunar Gemini, Spaceflight Histories, Aeryn Avilla, October 4, 2020

Lunar Landers That Never Were, Air & Space Magazine, Tony Reichhardt, January 1, 2008

I hope so Dave!! APPOLLO... what a project! Those were the days!! I do hope to buy the Bubble LEM one day along with other stuff by you!

Ahh those nagging little blunders of art! Cheesy for the sake of cheesy? Hmm? I do like how you point these out Dave. I even saw a blunder you made back on the Skylab series! I hope you fixed it!

No one is perfect so don't feel bad! Your care in your work is first rate! Have pride in how well you have produced your creations! I love your LM bubble gum strip!! If I were not in destitution I would buy several of your creations, especially the LM bubble gum strip!! I love that that one!