Exploring the intersection of spaceflight history, pop culture, and space art.

This edition of Creating Space extends the commemoration of the fiftieth anniversaries of the Skylab missions with a continuation of the discussion about the space station’s early development. This time, I talk about the Apollo boosters that were being studied in the early 1960s and the stages that made up the rockets, one of which would be chosen to house the Skylab Orbital Workshop.

Are you new to Creating Space? It’s the NERDSletter that explores the intersection of spaceflight history, pop culture, and space art. You can find this and all other posts at creating-space.art.

Boosting the Workshop

In the first post of my series on Skylab, The Origins of Skylab, I wrote about the early plans for a U.S. space station that was envisioned as part of the original proposed timeline for the Apollo program.

Before delving further into Skylab’s design evolution, it is worth taking a step back into the design process that led to the Apollo Saturn booster rockets that would ultimately launch Skylab and its crews into space.

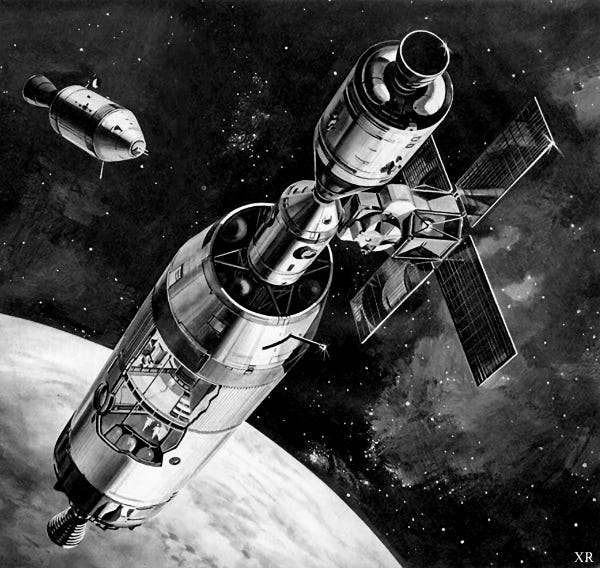

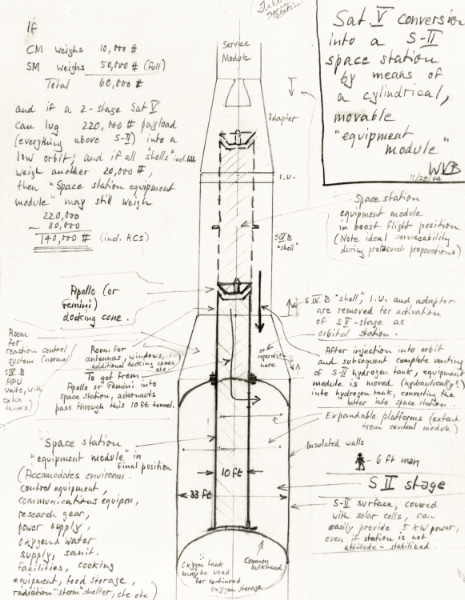

Wernher von Braun’s 1959 proposal for an Earth orbiting space station leveraged the launch capability and volume of the massive Apollo Saturn V rocket. It called for a Saturn V to be launched and then, once in Earth orbit, the second stage would be evacuated of any unused propulsion fluids and serve as the space station module. The station’s scientific and habitation equipment would be carried in the empty third stage and then transferred into the larger second stage.

This contrasted from earlier wheel-shaped space station concepts popularized by von Braun and others earlier in the 20th century. The wheel-shaped structure would have required manual assembly in orbit, constructed from components launched on multiple rockets. The Saturn V approach made it possible to rely upon only a single launch for the station, itself, and minimal assembly once in orbit. In either case, astronaut occupants would ride to the station on separate launch vehicles.

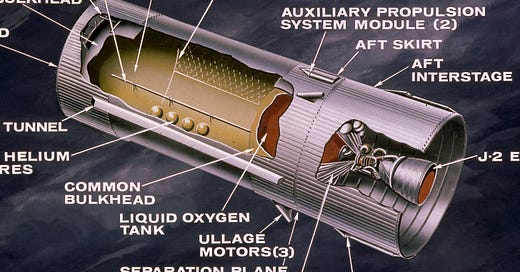

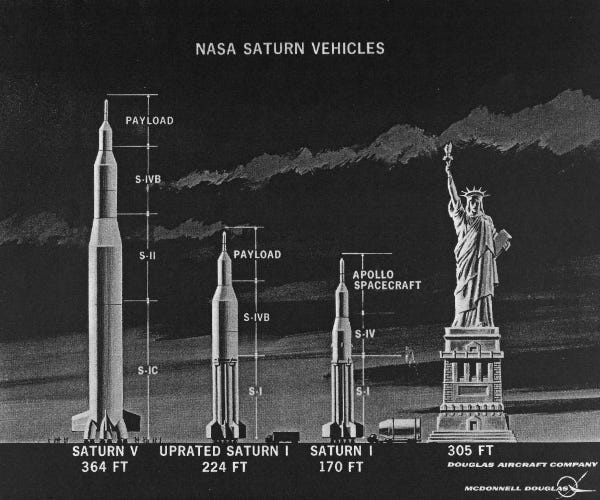

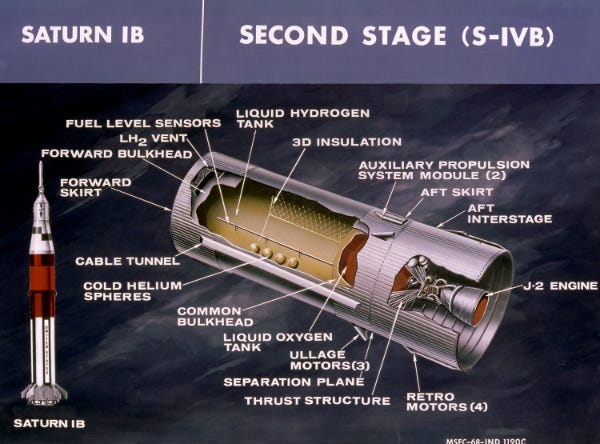

By the early 1960s, the design concepts for the Saturn family of rockets were firming up. The three-stage Saturn V rocket, destined to carry astronauts to the Moon, would be supplemented by an uprated version of the much smaller two-stage Saturn I rocket, later renamed Saturn IB. The two configurations would share a common upper stage called S-IVB.

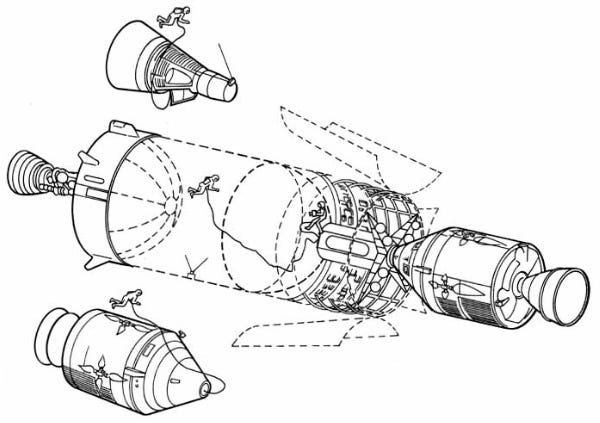

The favored Skylab workshop configuration would eventually have the S-IVB stage serving as the main space station volume, instead of the Saturn V’s second stage.

There were some studies that investigated using the smaller Saturn IB rocket to launch Skylab, instead of a Saturn V.1 In such a case, the propulsive thrust of both the Saturn IB’s first and second stages would be required to reach orbit. That meant, of course, that both stages would have to be fueled and configured with their propulsion systems, as usual. Thus, the configuration was referred to as a ‘Wet Workshop’.

The equipment for the space station operations would be carried on top of the S-IVB inside the cone-shaped Spacecraft Lunar Module Adapter (SLA).

If you see an early design sketch or model of Skylab that includes an engine, it would use the Wet Workshop approach to achieving orbit.

Advanced Mathematics: When 2 Equals 3 and They Both Equal 4

At this point, you may be wondering about the numbering systems used by NASA for the Apollo rockets and their stages. Why, for instance, was the second stage of the Saturn IB and the third stage of the Saturn V called the S-“FOUR”-B? And why, for that matter, were the two rockets used for Apollo numbered “one” and “five”?

NASA’s numbering system for its Apollo rockets and their stages is a result of the iterative conceptual design process that has been typical in the engineering world for decades. Engineers are often known as perfectionists. This trait is an arguably necessary one in order to produce products that are effective, economical, and safe. Engineering design is an iterative process. In professional industry, it has likely never been the case where someone sat down and drew something that went straight to manufacturing. We never get it right the first time. Someone will always be there to point out where a design falls short in some way. Or, the customer may change their mind. Or, the requirements may change. Or, money or politics may necessitate a change in direction. In engineering, change is inevitable.

Knowing that iterative changes are part of the process, it should come as no surprise that the Apollo Saturn rockets went through several iterations during their years of engineering studies. Each new set of rockets in a design cycle was identified with a unique letter, and each individual rocket in the family was numbered.

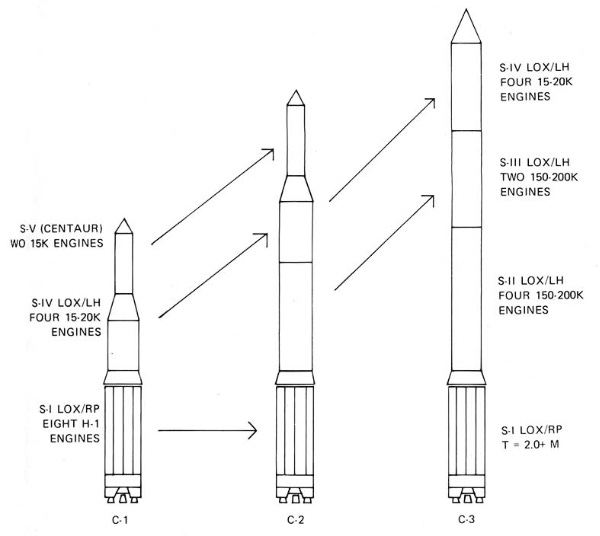

The initial Apollo rocket concepts for Apollo were labeled ‘A-1’ and ‘A-2’. By the time of the third major iteration, the ‘C’ family of Apollo rockets grew to five different sizes, each one containing a different number of stages.

The C-series of Apollo rockets used a “building block” concept where available hardware was leveraged as much as possible. They were configured to use a common first stage, consisting of a cluster of Redstone booster tanks surrounding a single fuel tank from the Jupiter class of rockets. Additional common stages were shared and distributed among the family.

At one point in the design evolution, the stage numbering was based upon the Saturn C-3 configuration. The four stages of the Saturn C-3 were named ‘S-I’ through ‘S-IV’, with ‘S’ likely standing for ‘stage’ and the Roman numerals counting the stages from the bottom up. These were pronounced “ess one” through “ess four”. Kudos to NASA for using a sensible numbering scheme ... at least for this one rocket.

The smaller Saturn variants, C-2 and C-1, would omit some intermediate stages shortening the rockets and making them suitable for less demanding missions. They would also add a common fifth stage based upon the Centaur. The C-1 variant is of interest because it is the closest configuration to what would eventually become the Saturn IB. The C-1 would omit the second and third stages from the C-3, leaving the S-1 and S-IV stages, and adding the S-V Centaur-based stage. Refer to the diagram illustrating the first three launch vehicles in the C-series.

Here is where the stage numbering relates to Skylab. As the designs for the Saturn rockets matured, the nomenclature for the stages carried over. But, not all the stages made it through to the final design configurations.

The two rocket configurations that ultimately flew on the crewed missions were called the Saturn IB and the Saturn V. The Saturn IB (pronounced “saturn one bee”) was descended from the C-1. It used an advanced S-I first stage and an S-IVB (pronounced “ess four bee”) for its second stage. The third stage was omitted and replaced with the payload – the Apollo spacecraft.

The Saturn V (pronounced “saturn five”) was descended from the C-5. Its large first stage was called ‘S-IC’. Its second stage was sensibly named ‘S-II’ (but a different S-II than was on the early ‘C’ configurations). And its third stage used the S-IVB from the Saturn IB. Again, topping it all off was the Apollo spacecraft payload.

So, the second stage of the Saturn IB was the same as the third stage of the Saturn V, and it was called S-IVB. The S-IVB stage would ultimately be chosen to house the Skylab workshop, and it would be launched on a Saturn V.

In a future post, I will discuss some of the many configuration variations for the Skylab orbital workshop, itself, that were studied by NASA and its contractors.

Art News

Here is your reminder that my space-inspired artwork, Moonlight Dreams, is part of the Art+Flight celebration at the Museum of Flight in Seattle, Washington. The celebration runs from June 10, 2023 through January 7, 2024.

In case you haven’t yet read about the exhibition and my artwork that is displayed, refer back to the following two posts to get filled in on the facts.

Art News from Moonlight Dreams post, June 4, 2023

Art News from The collectSPACE Insignia post, July 8, 2023

Art+Flight is free with Museum admission.

Open Daily, 10:00 AM to 5:00 PM

Admission FREE 5:00 PM to 9:00 PM the first Thursday of every month.

The Museum of Flight is located at 9404 East Marginal Way South, Seattle, WA 98108.

My space-inspired art portfolio can be found at pixel-planet-pictures.com. You can also follow me on Instagram (pixelplanetpics).

Do you know fellow Space Geeks who might enjoy Creating Space? Invite them into this space, too!

Did you miss a post? Catch up here.

If you enjoyed this article please hit the ‘Like’ button and feel free to comment.

A special offer for readers of Creating Space ...

If you’ve been reading down to the bottom of each post, you know that I have a website called Pixel Planet Pictures where I display and sell my space-inspired artwork. I invite you to visit my site.

If you are considering adding some of my artwork to your collection, I have good news for you.

As a special thank-you for reading Creating Space, I am offering a discount on my artwork.

Simply use code CREATINGSPACE15% for 15% off your entire order from the Pixel Planet Pictures shop.

All images and text copyright © Dave Ginsberg, unless otherwise noted. All rights reserved.

Wet workshop, https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Wet_workshop&oldid=1149925216 (last visited Aug. 16, 2023).